Introduction

Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) has long been celebrated in Finland as her country’s finest inheritance. Born in Helsinki, Schjerfbeck showed precocious artistic talent as a child, and was soon enrolled in a drawing class at the Finnish Art Society. Her ambitious early canvases honoring Finland’s history won her grants to study in Paris, where she spent several years under the tutelage of notable French naturalist painters.

Returning home in the early 1890s, first to Helsinki to teach and then to remote Hyvinkää to care for her aging mother, Schjerfbeck abandoned naturalism and pared down her figure paintings and still lifes to near abstraction. As she simplified her subjects, she intensified her process. By mid-career her artistry was bound to the materiality of her work, testing the medium of paint in a slow and deliberate way by adding and subtracting layers.

Schjerfbeck overcame many challenges in her eighty-year career, including chronic illness and political turbulence. Throughout, she persevered, writing to her confidant, Einar Reuter: “Painting is difficult, and it wears you out body and soul when it doesn’t come out right—and yet it is my only joy in life.” This exhibition introduces to global audiences an extraordinary Nordic modernist who realized her own unique vision with passionate determination.

All works in the exhibition are by Helene Schjerfbeck.

Early Years

Schjerfbeck’s youth was marked by travel and training. Recognized as a prodigy at an early age, she won several grants to study in Paris, and by the time she arrived in France she was painting with extraordinary proficiency. Many of the early figure studies were painted in the art schools of Paris while the more sentimental genre subjects reflect her rural travels to Concarneau in Brittany and later St Ives in Cornwall. Schooled among artists working in naturalism, she made figure paintings and landscapes that followed in step. Within a few years, she was showing paintings at the Salon, Paris’s annual juried art exhibition. By the mid-1880s her pictures were testing the boundaries of conservative painting. In View of St Ives (1887), she plays with scale and perspective, albeit through a sentimental lens. In Clothes Drying (1883), she is already painting her subjects ethereally and challenging the viewer to understand her deviation from straightforward landscape painting. Finnish journalists, unable to classify the painting as a landscape, dismissed it out of hand.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Honoring Finnish Heritage

Among Schjerfbeck’s defining early paintings are powerful narratives, including several commemorating Finnish history. It was incumbent on Finnish artists to paint episodes of their country’s history, often illustrating scenes of war. After centuries of Swedish occupation, followed by Russian rule, Finland was developing and celebrating its own heritage and cultural identity. A history painting won Schjerfbeck a grant to study in Paris. Later, her compelling allusion to the Jewish festival of Sukkot earned her entrée to the Paris Salon in 1883. Though still-life painting was less of a draw, Schjerfbeck undertook several pictures in that vein, clearly attentive to the robust examples by Edouard Manet (1832–1883) and others on exhibition in Paris.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

A Modernist Language

In 1902, Schjerfbeck moved to Hyvinkää, a small railroad town several hours north of Helsinki, to care for her aging mother. It was the isolation of this rural setting that enabled her to plumb her creative impulses. In modest accommodations and without access to professional models, she painted some of her most affecting canvases, often single figures dressed in black with little color to interrupt their dark silhouettes. Her mother, despite having no interest in her daughter’s vocation, was co-opted to model on several occasions.

By this point in her career, Schjerfbeck had radically redefined her aesthetic language. Soft brushwork characterizes these quiet paintings. Whether sitting or standing, reading or sewing, her subjects fill the picture plane and avert their gaze. Occasionally playful, occasionally bathed in raking light, her figures appear lost in thought and lost in time. Schjerfbeck investigates formal language—light, space, volume—not the soul of the sitter. She told her models to look away as she painted them, demanded their silence, and refused to show them the end result. Essential to her practice at the start of a painting, the models were later dismissed when Schjerfbeck’s inventive powers took charge.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Models and the Power of El Greco

In this sequence of portraits from the 1920s and 1930s, only Schjerfbeck’s nephew, Måns, is identified by name. The artist rarely noted a sitter’s name in her titles, but sometimes referenced their origin and, by association, their nationality. It is very likely that she suppressed her sitters’ identities for the same reasons she eschewed mimetic portraiture: In the few instances when she strove to transfer a likeness to canvas, her efforts often frustrated her until she got it right. Many of her sitters sport modish dress, evidence of Schjerfbeck’s lifelong interest in French fashion. After reading a 1912 article in an art magazine, she fell for the paintings of El Greco (1541–1614). Though she had no access to the originals, she worked up rather stylized transcriptions of his Madonnas and other sacred subjects, a preoccupation that intensified during World War II.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Italian Travels

In 1894, the Finnish Art Society sent Schjerfbeck to Vienna and Florence to copy works by the painters Holbein, Velázquez, Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, and Giorgione. It was in Italy that she painted several ethereal landscapes of Fiesole, perched on a hill above Florence. There, no doubt, she studied the beautiful yet degraded frescoes decorating the city’s churches. Those memories clearly influence her tender painting Fragment (1904). The canvas’s apparent deterioration dovetails with Schjerfbeck’s interest in manipulating her materials. In this instance, a redheaded girl posed for her in Hyvinkää. What followed was a process of adding and scraping away layers of paint, an experience she described in a letter to her dear friend and biographer, Einar Reuter:

The Red-Haired Girl got so greasy and shiny from being overpainted so many times, I wanted to scrape it all off—but then I didn’t have the nerve. I wanted to bury her in the ground to get rid of the shine, but I hadn’t the nerve to do that either, I had no idea what the result would be. And I didn’t dare paint on the background, it was better for it to stay that way. Cowardliness—fragment.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Still Lifes

Spanning fifty years of Schjerfbeck’s career, the still-life paintings in this gallery illustrate the artist’s shifting creative language. Blue Anemones in a Chip Basket (1892) recalls her Parisian training in naturalism and exposure to Impressionism—the French painter Henri Fantin-Latour comes to mind. The Red Apples (1915), unique in Schjerfbeck’s career for its glowing palette, demonstrates the artist’s distinctive technique of layering and removing paint to achieve complex structures. By the 1930s, the artist had reduced her still-life palette to more somber tones, exploiting her fruits to further her surface experiments. In her final still life, painted in 1944, blackening apples metaphorically reference the devastation of World War II and the chaos of upheaval. The apples no longer bear recognition.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Evolving Likenesses

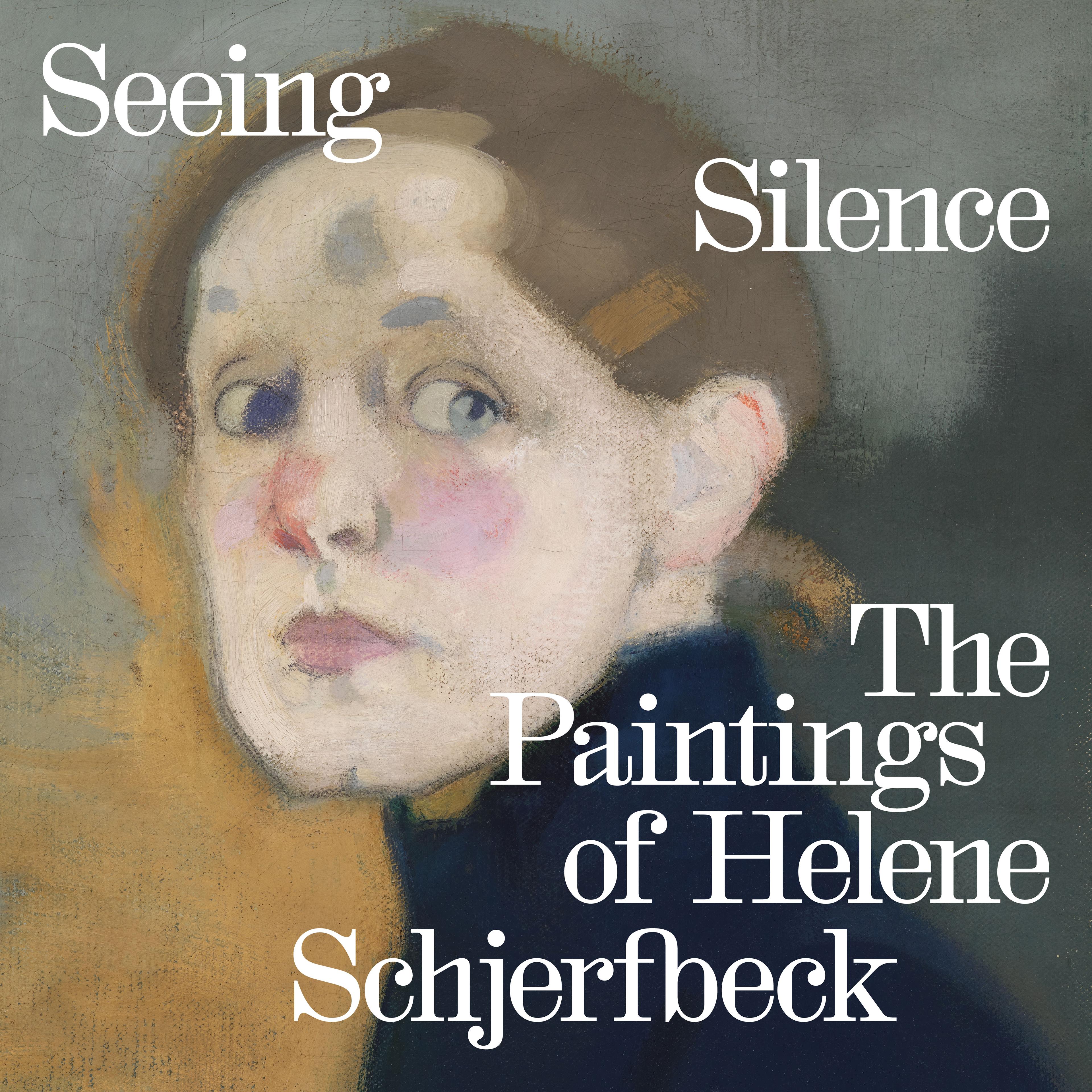

Helene Schjerfbeck interrogated her likeness in forty self-portraits across her lifetime. Her canvases trace the arc of her artistic development as they materialize her physical growth and decline. From youthful expressions in a naturalistic language to facial distortions that anticipate the haunting finale of this series, Schjerfbeck captures her self-image with increasing idiosyncrasy and self-confidence. By mid-career she is signing her name in prominent lettering. In Self-Portrait, Black Background (1915), a paintbrush interrupts the otherwise stark framework of her many bust-length self-studies. That same year, she experimented with silver leaf in a rather stylized likeness that hints at her fascination with contemporary fashion. Schjerfbeck’s introduction of new materials and painting processes energized her practice for much of her career.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Painting Mortality

As war raged throughout Finland in 1944, Schjerfbeck’s art dealer persuaded her to relocate to Sweden. Painted in the hotel room where she spent her last years, isolated and alone, the self-portraits on view here express the effects of age and illness. Few other series in the history of modern art articulate mortality with such candor. In the four likenesses on this wall, the artist uses thin, glazed color that soaks entirely into the canvas in some instances. Devoid of saturated hues and generally monochrome, the paintings are at once haunting and magnificent. Schjerfbeck never lost her wish to return to Finland. After she died, in 1946, her body was returned home for burial.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.