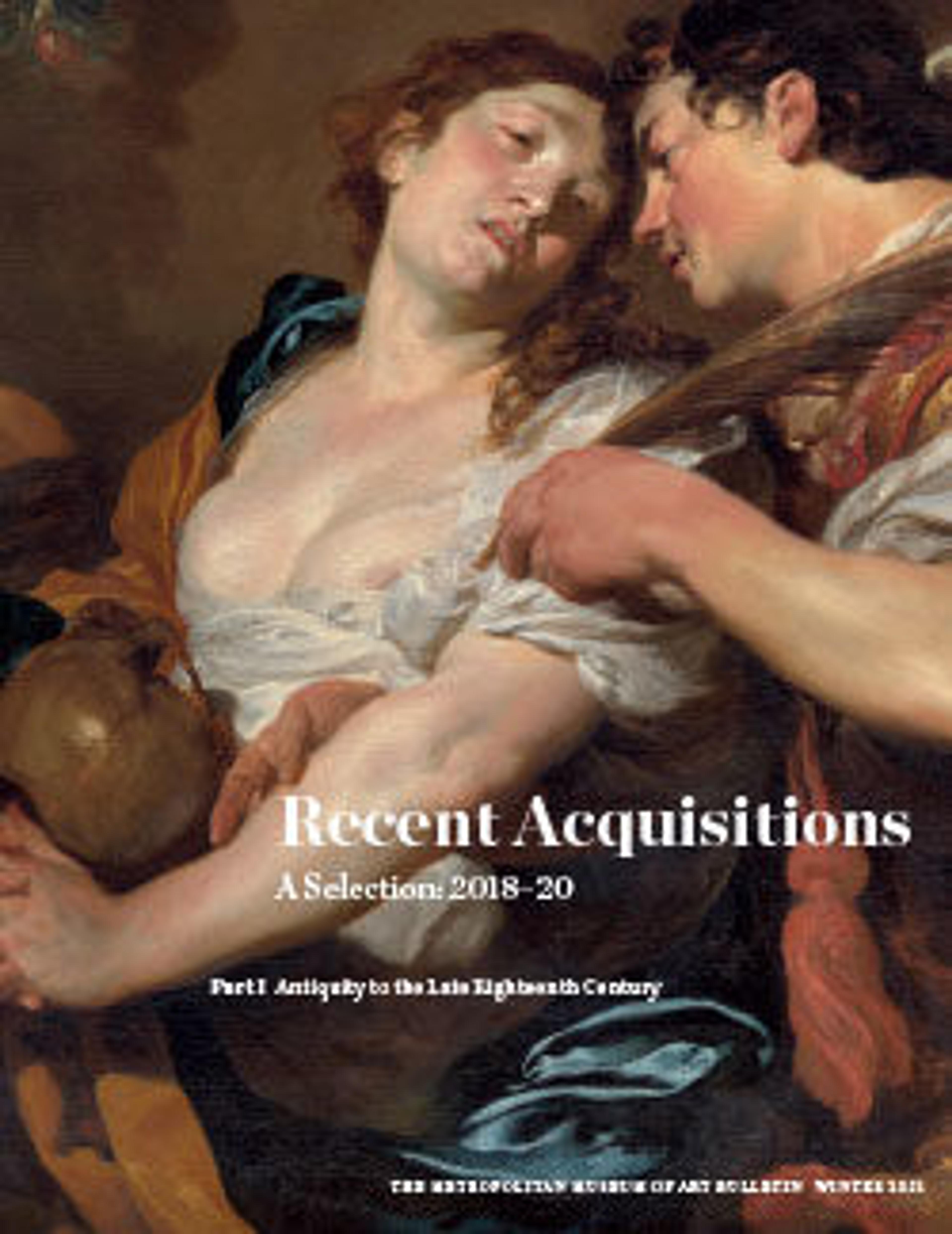

A Bouquet of Flowers

Artwork Details

- Title: A Bouquet of Flowers

- Artist: Clara Peeters (Flemish, Mechelen ca. 1587–after 1636 Ghent)

- Date: ca. 1612

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 18 1/8 × 12 5/8 in. (46 × 32 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Howard S. and Nancy Marks, Friends of European Paintings, and Mr. and Mrs. J. Tomilson Hill Gifts, Gift of Humanities Fund Inc., by exchange, Henry and Lucy Moses Fund Inc. Gift, and funds from various donors, 2020

- Object Number: 2020.22

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

5237. A Bouquet of Flowers

Clara Peeters, 1612

KATHY GALITZ: I like that she signed her work so that she couldn’t fall into oblivion. She’s already thinking about her reputation and being remembered as a woman artist.

Hi. I’m Kathy Galitz and I’m an art historian and educator at the museum.

NARRATOR: There’s her signature: Clara Peeters, right at the bottom by the stone ledge: below the three little blue flowers known as forget-me-nots.

KATHY GALITZ: She really helped develop this genre in the 17th Century, with the idea that often what artists were painting was, you know, more than meets the eye.

And you see that in this still life, because the flowers, as lush and beautiful as some of them are, if you look really closely, some of them are wilting, some of them have fallen and have dropped to the table. And it makes you realize this is beautiful, but it’s not going to be beautiful forever, just like we’re not going to live forever either.

NARRATOR: Despite its nuance and complexity, still-life painting was often placed at the bottom of artistic hierarchies at the time. Associate Curator Adam Eaker.

ADAM EAKER: Because it didn’t include any human figures, it didn’t require students to study live models or to read ancient texts. It was considered to be the least intellectual genre of painting…

NARRATOR: ...and, not unrelatedly...

KATHY GALITZ: It was often then a genre that was associated with women and deemed, you know, acceptable for a woman to paint.

ADAM EAKER: Women were, in most cases, excluded from studying the live model, which was a key component of an artistic education in this period. But it wasn’t considered proper for young women to be around naked men posing in an academy. And so instead, what they were able to become proficient at depicting, was more likely to be still life subjects.

This painting is a recent acquisition by The Met, purchased in 2020, and it very much reflects our ongoing project of expanding, or questioning the canon of European painting.

KATHY GALITZ: I think that’s something really, really important, to show other women artists who’ve been forgotten.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.