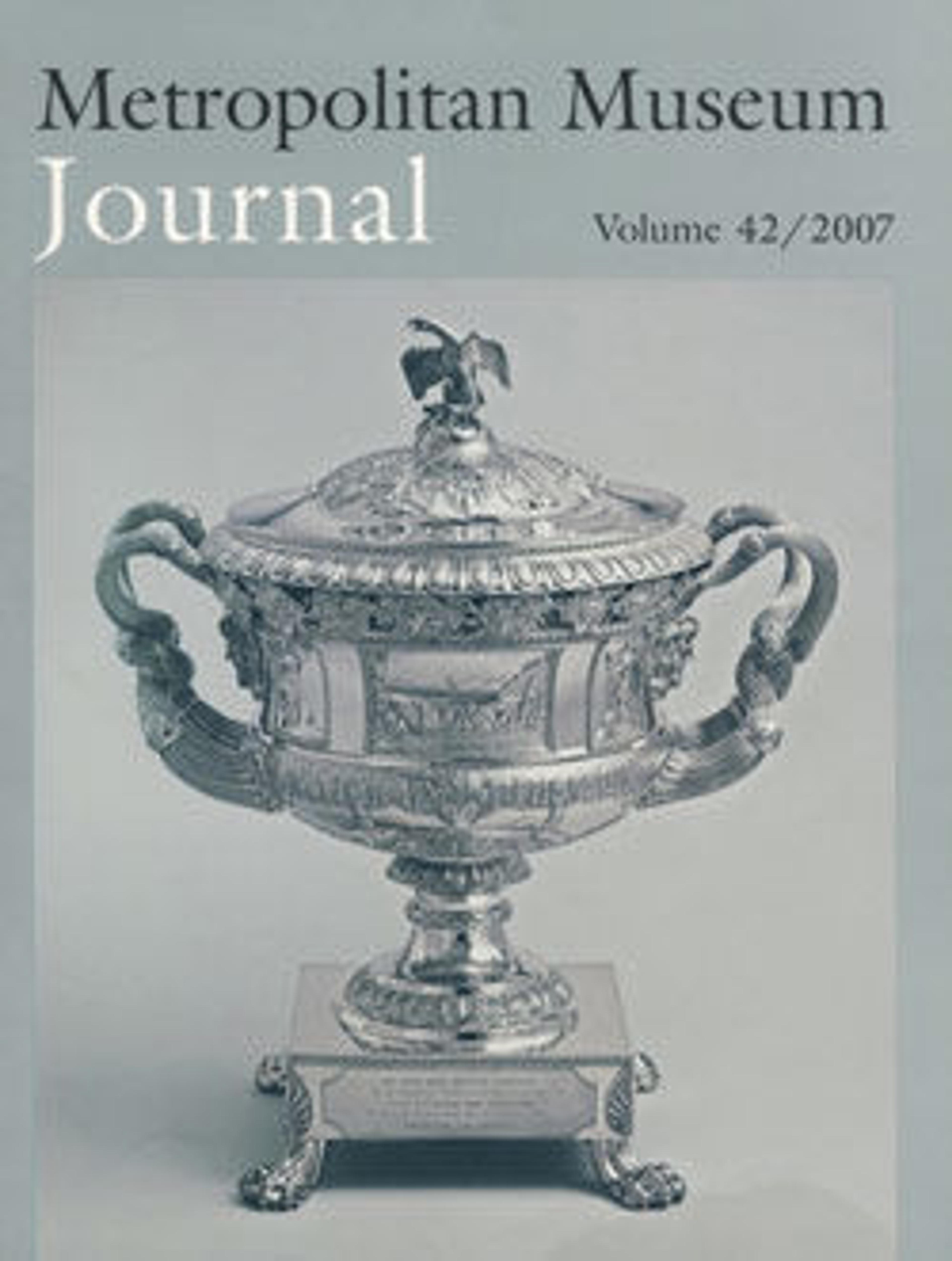

Presentation Vase

The vases are marked by the partnership of Thomas Fletcher and Sidney Gardiner, who relocated from Boston to Philadelphia in 1811 in search of greater commercial success. Excellent entrepreneurs, they soon became the leading American supplier of presentation silver, as well as retailing a wide range of imported goods, such as brass, cutlery, and lighting fixtures. Fletcher and Gardiner are representative of the large urban firms that became increasingly common during the nineteenth century.

Artwork Details

- Title: Presentation Vase

- Maker: Thomas Fletcher (American, Alstead, New Hampshire 1787–1866 New Jersey)

- Maker: Sidney Gardiner (American, Mattituck, New York 1787–1827 Mexico)

- Date: 1825

- Geography: Made in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

- Culture: American

- Medium: Silver

- Dimensions: 23 3/4 x 20 3/4 x 14 3/4 in. (60.3 x 52.7 x 37.5 cm); 401 oz. 1 dwt. (12473.9 g)

- Credit Line: Gift of Erving and Joyce Wolf Foundation, in memory of Diane R. Wolf, 1988

- Object Number: 1988.199

- Curatorial Department: The American Wing

Audio

4011.Presentation Vases, Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner (1824 & 1825)

NARRATOR: These silver vases, with gleaming images of native animals and the Roman gods of commerce and agriculture, hold contradictions for a modern audience. They were gifts for the governor of New York, who led efforts for the Erie Canal's construction.

They are clearly intended to celebrate a triumph. But at what cost?

Lemir Teron, associate professor at Howard University in the Department of Earth, Environment and Equity.

LEMIR TERON: To some folks, the Erie Canal meant economic expansion, westward expansion, manifest destiny, opening up commerce to the west at a much less expensive price. It meant that New York State was expanding and establishing itself as a global economic power.

NARRATOR: Looking closely at both sides of the vases, you’ll notice figures gazing out at peaceful scenes that belie a more complex history. Environmental Researcher Renée Barry explains.

RENÉE BARRY: There are different vistas here. On one of the scenes we see two people looking out over the Erie Canal. They seem to be admiring the Erie Canal as this magnificent work. There is another vista represented, of an indigenous man looking down at a tree that was chopped down, presumably for the construction of the Canal. He’s contemplating, I imagine, the deforestation that was necessary to make the Erie Canal. It’s important to really look at what ‘progress’ really means,what is the human and environmental cost to this progress.

LEMIR TERON: How did the decimation of New York State undermine the livelihoods, the commercial livelihoods, the social livelihoods, of Haudenosaunee and Native peoples.

If we are going to really look at this piece, then let’s acknowledge that there were some awful things that happened to get that westward expansion. Things like ethnic cleansing, enslavement. The decimation of native peoples through acts of genocide. You wouldn’t have an Erie Canal unless you had that, so in addition to having a god of commerce or a god of agriculture, it'd probably be more suitable to also include Mars, the god of war.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.