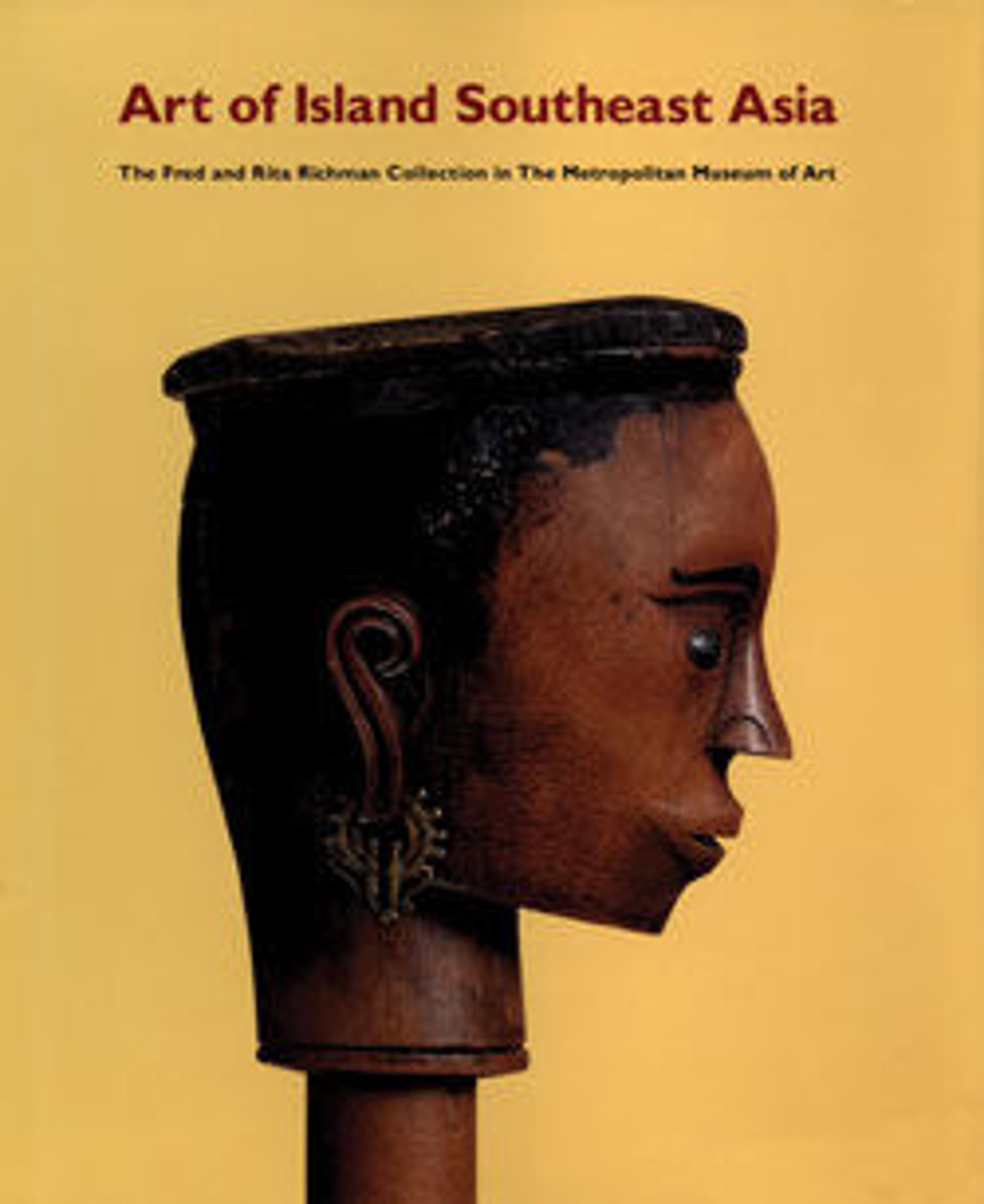

Dadatoko (ceremonial dance shield)

Artwork Details

- Title: Dadatoko (ceremonial dance shield)

- Artist: Halmahera Island artist

- Date: late 19th–early 20th century

- Geography: Indonesia, Maluku Tenggara

- Culture: Halmahera Island

- Medium: Wood, shell, porcelain, paint, resin

- Dimensions: H. 20 × W. 3 × D. 3 in. (50.8 × 7.6 × 7.6 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Implements

- Credit Line: Gift of Fred and Rita Richman, 1988

- Object Number: 1988.143.32

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1727. Dadatoko (ceremonial dance shield), Halmahera Island artist

Wim Manuhutu

WIM MANUHUTU: The shape of the shield immediately shows that if you want to use it effectively, you will have to be a trained fighter.

My name is Wim Manuhutu. I'm a historian and a curator. I am located in the Netherlands. My father hails from the Moluccas…

KATERINA TEAIWA (NARRATOR): …as does this very narrow dance shield.

WIM MANUHUTU: The shield, and especially shields that are older, are considered to be basically embodiment of this tradition of being able to defend yourself, being able to go to war. And also in the war dance, the Cakalele, these shields play an important role.

And even here in the Netherlands we see that among young people, third, fourth generation, this dance is definitely still considered to be powerful.

KATERINA TEAIWA: It’s significant that this shield is decorated with both shells and porcelain.

WIM MANUHUTU: And the fact that there are ceramics involved is, of course, also a sign of the fact that the Moluccas were not ever cut off from the outside world, because we see that even in very closed-off communities, people would have porcelain. And other ceramics that theyself did not produce, but by trade with coastal communities, got their hands on. That people from China already, hundreds of years ago, prior to the arrival of the first Europeans, sailed all around the world, but also sailed to Maluku.

KATERINA TEAIWA: Later, Dutch colonizers extracted nutmeg, mace, and cloves native to the islands, monopolizing the spice trade and its profits.

WIM MANUHUTU: That now seems to repeat in the post-colonial modern nation state of Indonesia, where people see: Well, if we see where the profits go to, it's still not that we are profiting.

KATERINA TEAIWA: Today, Moluccan people’s livelihoods and ways of life are threatened by modern industry, extraction, and climate change. But this shield—and the canoe prow nearby—remain powerful symbols of Moluccan identity.

WIM MANUHUTU: So not specifically only for people living in Tanimbar when it comes to the prow, or in Halmahera in the north Moluccas when it comes to the shield, but they are something that we can actually be very proud of. And by having these objects in well-respected museums sometimes the issue of restitution comes up. But in other cases, people are very proud that in very prestigious places, there is a representation of Moluccan culture.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.