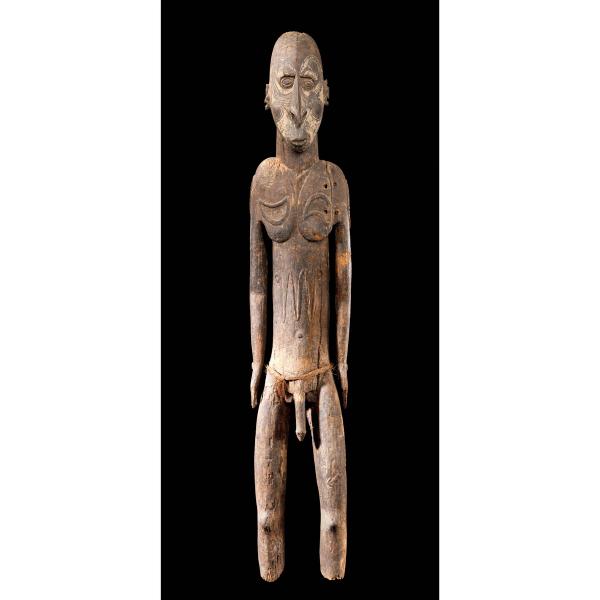

Ancestor Figure

This figure which bears the name Minjemtimi and is reputed to be ten generations old. It is said to have been made in the village of Kwalunggei. When warriors from neighboring Yamok village raided Kwalunggei, the figure is said to have come to life and fought the invaders until hit by a spear, which broke off its left arm (the wound is still visible as a repair). The wounded Minjemtimi fell to the ground and turned back into a wooden figure that was carried off by the raiders. In Yamok the figure was kept by the Ainggun clan in a ceremonial house in the hamlet of Wolembi. The marks on the abdomen represent rooster heads joined by a length of intestine and are similar to the ritual scarifications made on the bodies of initiated Sawos men.

Artwork Details

- Title: Ancestor Figure

- Date: 19th century or earlier

- Geography: Papua New Guinea, East Sepik Province, Yamok village, Middle Sepik River region

- Culture: Sawos people

- Medium: Wood, paint, fiber, ferrous metal

- Dimensions: H. 72 x W. 12 3/4 x D. 9 7/8 in. (182.9 x 32.4 x 25.1cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

- Object Number: 1979.206.1561

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1744. Ancestor figure, Sawos artist

Wylda Bayrón

KATERINA TEAIWA (NARRATOR): Walk around this ancestor figure and look at the marks on the left shoulder, back, and thigh. They resemble the crocodile scars made on Sawos men during skin cutting initiation ceremonies. In this culture, crocodiles symbolize power.

WYLDA BAYRÓN: The scarification pattern starts at the nipples, and those are the eyes of the crocodile. And then it continues through the arms of the human to exemplify the paws of the crocodile and through the back and the legs.

My name is Wylda Bayrón, and I’m an indigenous Taíno and Arawak from Puerto Rico. And I am a cinematographer and photographer. I’ve been photographing New Guinea for the last decade.

So, New Guinea has a lot of secret societies, male secret societies, and as a female, there’s usually a boundary that you can’t cross. Thankfully, somehow in the middle Sepik in Yamok village, I was able to be entrusted to photograph a male skin cutting initiation.

This takes hours. They're being cut for a long time. There's a level of pain there that is... transcendental.

One of the most beautiful moments was the end. After hours of skin cutting and blood and flesh being opened and grunts and screams, they take out Tagasso oil with a feather and apply it all over their backs. And it’s a beautiful final moment of respite for the boys.

After that, they then go into the spirit house, which has smoke, and they put packed clay on their scars as well. And that starts the process of healing.

And you would not believe the difference of that young man to that man after 3 to 6 months in that initiation ceremony. It's just incredible. Almost like the smile fades and the innocence fades, and there is a real gravitas to the existing human at the end of that. It's very powerful.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.