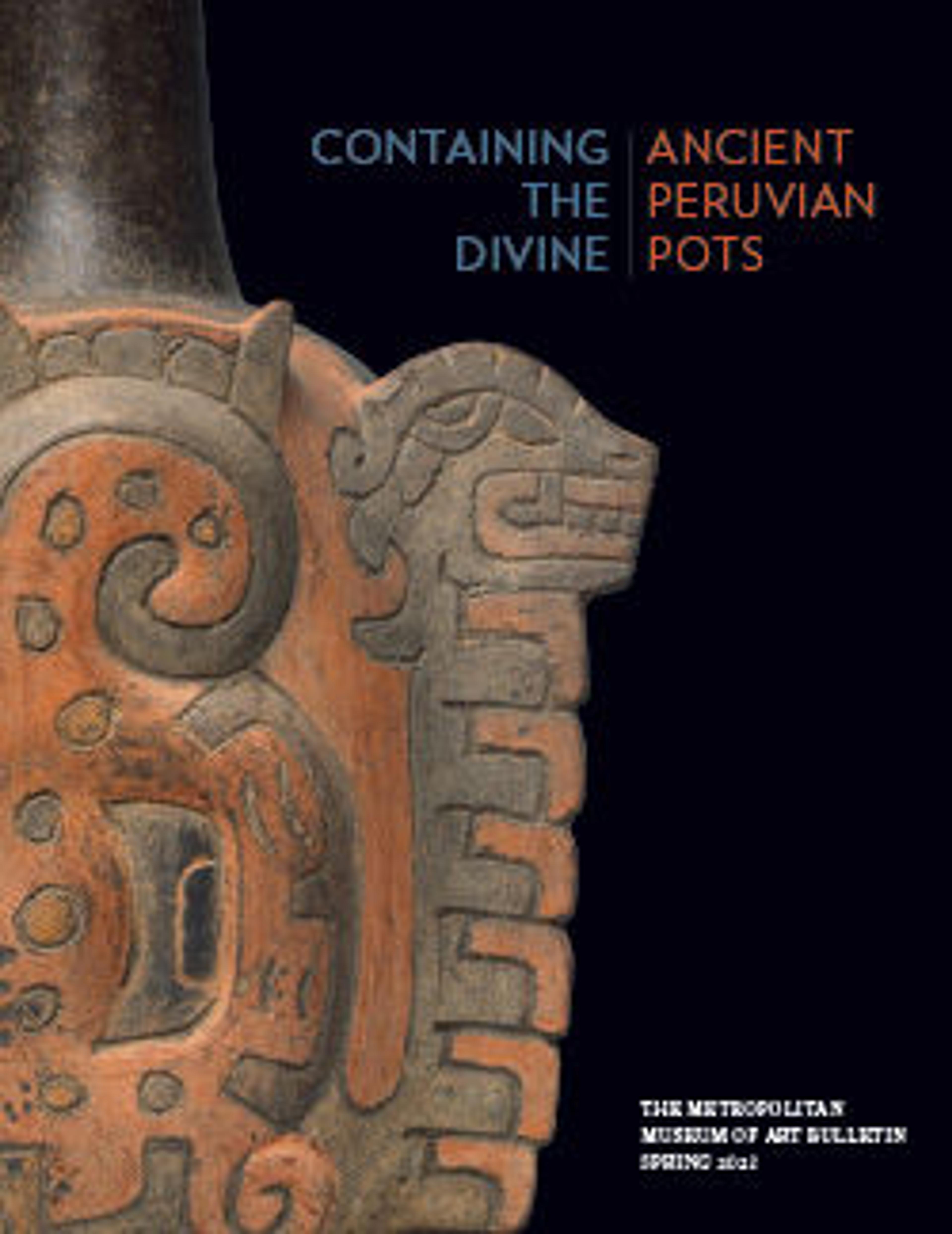

Stirrup-spout bottle

Cupisnique artists preferred a muted palette, usually the color of the fired clay itself, but they created visual interest by contrasting smooth and textured surfaces. On this stirrup-spout bottle, the unornamented sections were created by carefully smoothing the clay when leather-hard, and then burnishing it with a polishing stone (for an example of a polishing stone, see MMA accession number 1994.35.769). The textured areas were produced by adding appliqués and impressing a comb-like tool into the clay. The combination of smooth and textured areas is a visual and tactile reminder of the interior and exterior surfaces of Spondylus shells, a bivalve considered to be among the most precious ritual materials in the ancient Andes (see MMA 2003.169).

Hugo C. Ikehara-Tsukayama, Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial/Collection Specialist Fellow, Arts of the Ancient Americas, 2022

Further Reading

Burger, Richard L. Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992, pp. 90-99.

Burtenshaw-Zumstein, Julia T. Cupisnique, Tembladera, Chongoyape, Chavín? A Typology of Ceramic Styles from Formative Period Northern Peru, 1800-200 BC. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Norwich: University of East Anglia, 2014.

Elera, Carlos. "El complejo cultural Cupisnique: Antecedentes y desarrollo de su Ideología religiosa." Senri Ethnological Studies, No. 37 (1993), pp. 229-57.

Artwork Details

- Title: Stirrup-spout bottle

- Artist: Cupisnique artist(s)

- Date: 800–500 BCE

- Geography: Peru, North Coast

- Culture: Cupisnique

- Medium: Ceramic

- Dimensions: H. 9 5/8 × W. 5 1/2 × D. 5 1/2 in. (24.4 × 14 × 14 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Containers

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1969

- Object Number: 1978.412.40

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1644. Stirrup-spout bottle, Cupisnique artist(s)

Hugo Ikehara-Tsukayama

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: Pottery became an object that carried meanings and ideas. In many ways, ceramic containers became the ideal canvas for displaying images and pottery became a ritual object and finally a political tool to spread ideas or showcase authority and power. My name is Hugo Ikehara-Tsukayama. I’m a senior research associate for ancient American art.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK (NARRATOR): This bottle, made around 3,000 years ago on Peru’s north coast, has a characteristic stirrup-shaped spout. This vessel shows a contrast between shiny polished surfaces and areas patterned to resemble the spiky exterior of the shell of a Spondylus—a marine bivalve mollusk.

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: The Spondylus was highly appreciated because its vibrant red color and as a ritual substance offered to ancestors and other divinized beings. In the 16th century it was considered the preferred food for the deities.

The Spondylus shell only grows in the warm waters of Ecuador to the north. So, to have a Spondylus 400 or 500 kilometers to the south implies there was a movement of these goods between communities.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Andeans brought large quantities and varieties of vessels to community celebrations or festivals, sometimes involving hundreds of guests.

HUGO IKEHARA-TSUKAYAMA: Maybe the organizers are demonstrating their ability as leaders because they can mobilize people under social networks to bring different kind of pot, bottles, bowls from close and from afar. You do that every single time you do these parties.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Archaeologists have unearthed assemblages of shattered pottery, the remnants of these celebrations. Leaders ceremonially destroyed the vessels at the close of gatherings—as a display of their power and authority—enabling and requiring new cycles of creation and giving. The destruction of these artworks prompted a demand for new vessels and instigated more artistic invention and innovation.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.