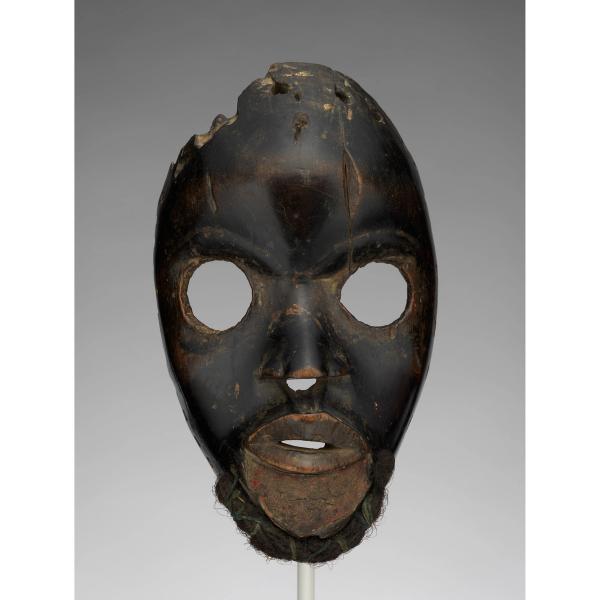

Gunyege face mask

Dan masks have been documented as the embodiment of at least a dozen artistic personalities. Among these are Deangle, who ventures into the village from the initiation camps to ask women for food; Tankagle and Bagle, who entertain through a range of aesthetically pleasing dances, skits, and mimes; Gunyege, whose mask is worn by a community's champion foot racers in competitions; and Bugle, who historically leads men into battle. With its wide circular ocular apertures and remaining of red ibers, this mask can be identified as Gunyege. During the races held each week of the dry season in the northern savanna, a runner wearing such a mask would chase a unmasked runner. If he managed to catch him by the neck and back, he kept his mask. If not, the unmasked runner would put on his own mask and, in turn, chase another competitor. At the end of the season, the runner with the most victories was proclaimed the champion.

Once they are divorced from their performance contexts, however, mask forms are difficult to identify. Performances of Bete and Wè masks may span the careers of many generations of wearers, contributing to the increasingly sacred status of these objects. A masquerade's vitality may also be transferred from one mask form to another. Over time, any respected Dan mask may eventually be elevated to the category gunagle, the mask that represents a village quarter, or gle wa, a judicial mask.

Artwork Details

- Title: Gunyege face mask

- Artist: Dan artist

- Date: 19th–mid-20th century

- Geography: Côte d'Ivoire or Liberia

- Culture: Dan peoples

- Medium: Wood, felt, human hair, cord, iron, clay, pigment(?), tukula(?)

- Dimensions: H. 8 3/4 in. × W. 5 in. × D. 2 7/8 in. (22.2 × 12.7 × 7.3 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1964

- Object Number: 1978.412.354

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1543. Face masks, Dan artists

Nimely Napla and Naomi Diouf

ANGELIQUE KIDJO (NARRATOR): Dan artisans of West Africa carved a range of expressive masks for community dance performances. Animated by the human body, the masks channeled the powers of spirit beings.

NIMELY NAPLA: My teacher told me, ‘When you get into a mask, you’re not the same anymore. You are a spirit because nobody know who is in there. Nobody know what you're coming to do.’ You are not Nimely no more. You are not that person.

I’m Nimely Vannie Napla. I’m from Liberia, West Africa. I’m a schoolteacher teaching music and art, and I’m a former director of the Liberia National Dance Company.

NAOMI DIOUF: I’m Naomi Johnson Diouf. I’m also from Liberia, West Africa. I’m now the executive artistic director for Diamano Coura West African Dance Company in the Bay Area.

My connection to dance started at five, six years old—they had a big ceremony at our house. The entire Grebo community, all of these people came, and they had this big dance celebration. And our ethnic group, one of our biggest dances we do is the war dance. That was my first connection with, wow, the dance is powerful, it's beautiful, and I was captivated by the music, the drums, and the horns, and everything else.

NIMELY NAPLA: I learned how to speak the language from the drum that were very unique for me. When we do it outside, I like the way because you're dancing, the drum is talking to you. You can be in the middle of the dance, the drummer says, "stop," you've got to stop, whatsoever your step is.

NAOMI DIOUF: There is a technique to African dance. The only way you can get it is to understand there are different ways to utilize the body that is technical, that is athletic and also aesthetic. I'm saying to people that, 'Yeah, ballet has a technique. So does African.’ And so it becomes a conversation to actually make people more aware.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.