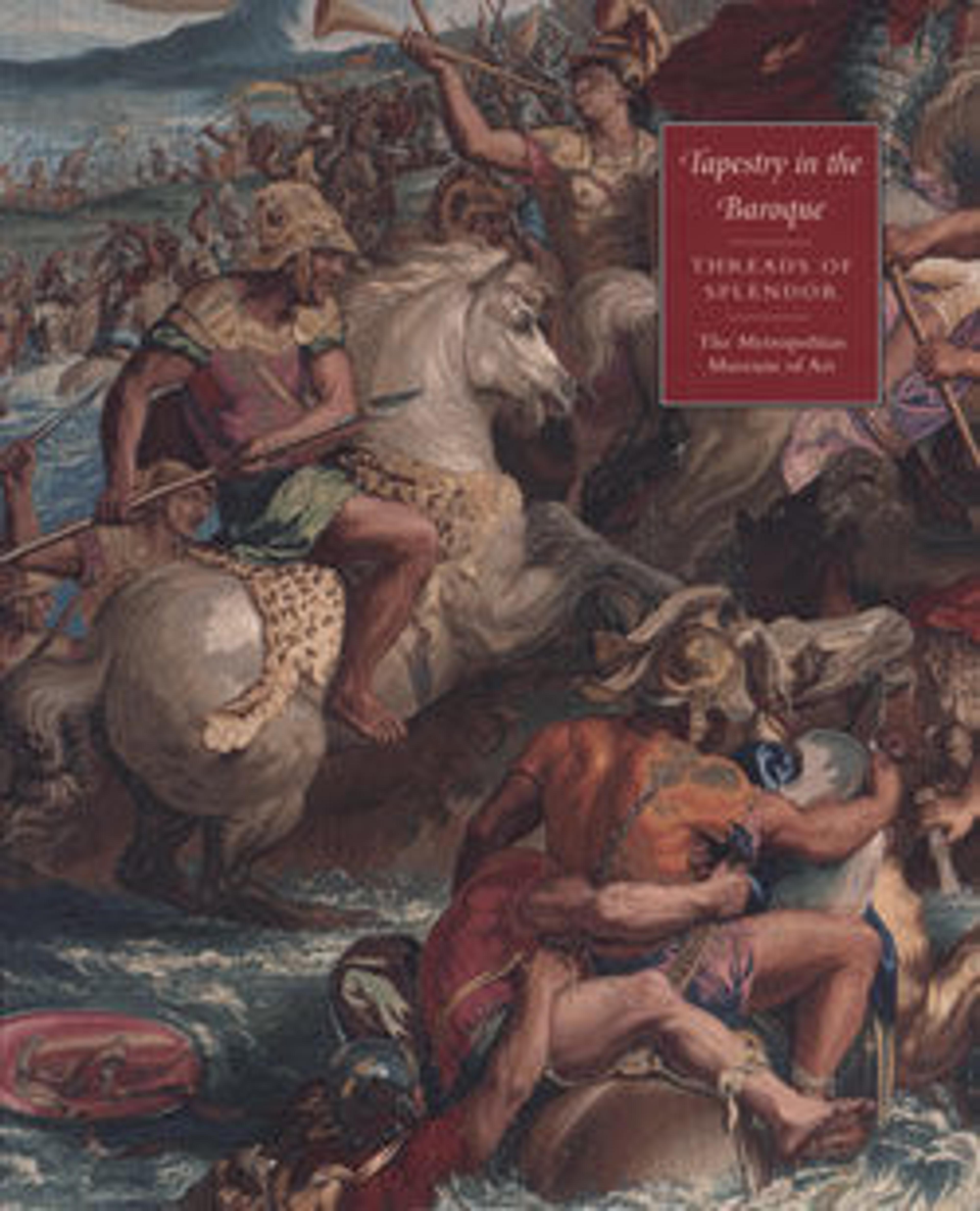

The Destruction of the Children of Niobe from a set of "The Horses"

Artwork Details

- Title: The Destruction of the Children of Niobe from a set of "The Horses"

- Designer: Frans Cleyn (German, Rostock 1582–1658 London)

- Manufactory: Probably made at Mortlake Tapestry Manufactory (British, 1619–1703)

- Patron: Henry Mordaunt (Drayton House, Northamptonshire, 1623–1697)

- Date: ca. 1650–70

- Culture: British, probably Mortlake

- Medium: Wool, silk (16-19 warps per inch, 6-7 per cm.)

- Dimensions: Overall: 152 × 232 (386.1 × 589.3 cm)

- Classification: Textiles-Tapestries

- Credit Line: Gift of Christian A. Zabriskie, 1936

- Object Number: 36.149.1

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Audio

402. The Destruction of the Children of Niobe from a set of "The Horses"

Gallery 509

NARRATOR: This monumental tapestry marks a new cultural moment, born of both entrepreneurial spirit and a booming economy. To produce it required extraordinary craftsmanship (and a budget to match). To commission it, was, for one monarch, a way of broadcasting his grand ambitions to Europe. The Met's Wolf Burchard:

WOLF BURCHARD: Tapestry weaving was hugely important in the Middle Ages, but the monopoly really was with Flanders and with Flemish weavers. And both the King of France and the King of England wanted to produce their own So they founded the Gobelins manufactory in Paris, at the very beginning of the 17th century, and the Mortlake tapestry manufactory outside London.

NARRATOR: Mortlake's studio hired the best émigré craftsmen available: Flemish weavers, as well as the German designer Frans Cleyn, who was brought on to oversee the complex productions. We can still appreciate them for their remarkable craftsmanship, such as the almost cinematic quality of the mythical scenes, populated with mind-bogglingly three-dimensional figures.

Who bankrolled these fantastic weavings, and why? Some clues: he had deep pockets, lofty tastes, and the patience to wait years for a work of art to be crafted to his specifications.

Meet King Charles I. Charles understood that art and design–be it clothing, paintings, or tapestries–were tools for power. And kings like him deserved absolute power. As he put it himself:

CHARLES I: Princes are not bound to give an account of their Actions but to God alone.

NARRATOR: Partially because of this belief, twenty years of civil war divided England. Charles is remembered not only as an iron-fisted ruler, but also as one of the day’s most important patrons and collectors. He wore his power on his sleeve, literally; you can find a painted portrait of him sporting a luxurious costume of gold and silver thread above the staircase behind you.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.